A new research reveals how the world’s largest pesticide companies earn billions of dollars a year from the sale of chemicals that pose a threat to human health and the environment.

Unfortunately we know that harmful chemicals are commonly used in agriculture all over the world for the joy and profit of large companies that trade their toxic products undisturbed.

The use of these highly dangerous pesticides (HHPs) is, according to data analyzed by Unearthed (a journalistic group funded by Greenpeace UK and the Swiss NGO Public Eye), greatest in poorer countries. As an example, in India, HHPs cover 59% of sales – a huge number when compared to the U.K. (11%).

The data processed by Phillips McDougall, the leading agribusiness analysts, comes from customer surveys and focused on the most popular products in the 43 countries where the largest number of pesticides are traded.

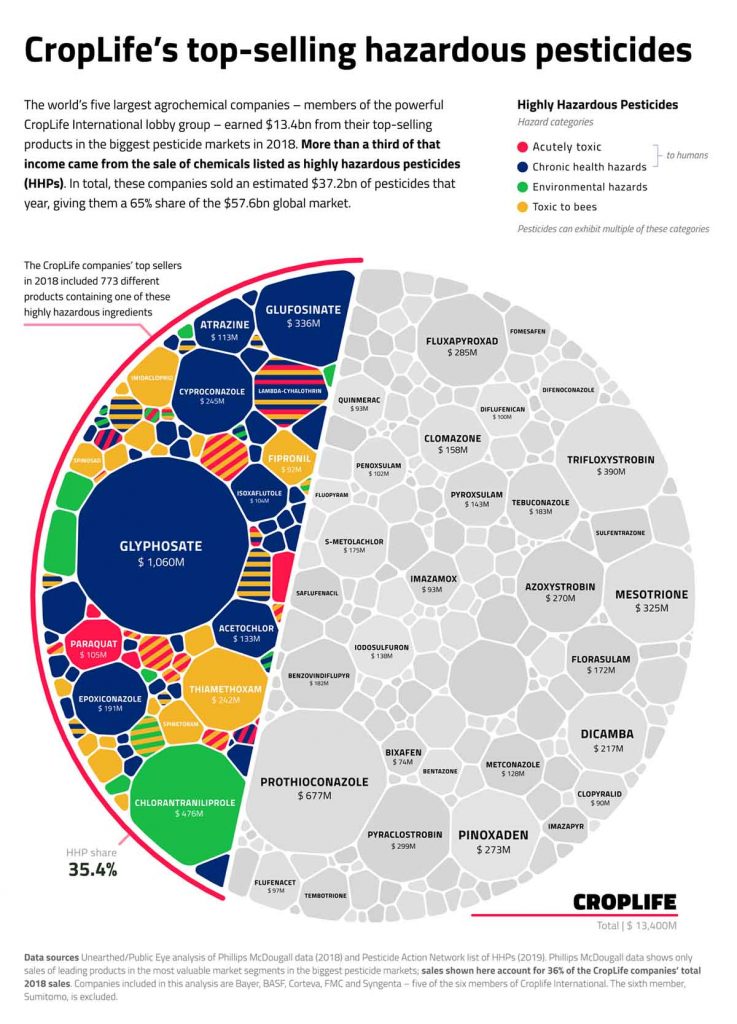

The pesticide market is essentially dominated by five companies: Bayer, BASF, Syngenta, FMC and Corteva (formerly Dow and DuPont). These companies sold $ 4.8 billion of HHP-containing products in 2018, which represents more than 36% of all their income, according to reports.

Bayer stated that the analysis was “misleading”, but refused to provide their own data. Other companies also contested the list of HHPs used.

Unearthed’s analysis calculated that almost a quarter of the sales of these 5 major companies concerned products containing pesticides related to negative effects on human health, including known or suspected carcinogens but also substances accused of increasing the risk of birth defects, while 10% came from pesticides toxic to bees (some now banned in European markets). Another 4% of sales related to chemicals that are highly toxic to humans.

By far the most valuable markets for these highly dangerous pesticides are the crops of raw materials such as soybeans and corn, used largely to provide animal feed for the meat industry.

There is also talk of 200,000 suicides that are attributed to pesticide poisoning every year, almost all in developing countries.

In short, this is a situation that cannot be ignored. The issue was also addressed in 2018 with a global survey by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, noting “various critical deficiencies” and the need by individual countries to strengthen the rules in order to “minimize their harmful effects on humans and the environment”.

Baskut Tuncak, UN Special Rapporteur on dangerous substances and human rights, said:

“It is inappropriate for companies to earn such significant income from HHPs in this day and age. The continued use of these products is unsustainable and is causing a multitude of human rights violations around the world. “

A 2017 report written by Tuncak accused pesticide trading companies of “systematic denial of harms”, “aggressive, unethical marketing tactics” and lobbying of governments, which has “obstructed reforms and paralysed global pesticide restrictions”. It also said the idea that pesticides were essential to feed a fast-growing global population was “a myth”.

Croplife International, the pesticide industry lobby group, has admitted that 15% of the chemicals its members sell are HHPs, but said many of these can be used safely.

“Our members support the [voluntary] FAO International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management,” said a CropLife International spokeswoman. “We support countries to identify, and if necessary, remove HHPs from their markets.”

But in response Keith Tyrell, director of PAN UK, said:

“Pesticide companies refuse to publish information on the ingredients contained in their products so the UN and others, including PAN, are forced to look solely at the toxicity of the active ingredient.”

Bayer also challenges the PAN list. For example, it includes glyphosate on its list based on the 2015 IARC conclusions that “it is probably carcinogenic to humans.” But Bayer says that glyphosate should not be on the list, based on the conclusions of other organisms, such as the European Chemicals Agency in 2017.

A Bayer spokesperson said that the different country-to-country sales reflect the different needs of farmers:

“Agriculture is very different from region to region due to different climates, pests, diseases and crops. In Brazil, for example, farmers must manage pests such as Asian Soybean Rust or insect pressure which don’t exist in Europe.”

In short, companies continue to make huge profits on harmful substances. How can we respond? We can help by spending our money ethically and buying local, organic products and, if at all possible, growing some of our own crops.

—

Sources: Unearthed, The Guardian